UK & DE Freight in 2024 and Beyond: A Supply Chain Logistics Case Study

Dive into the future of UK & DE freight: Adaptation, green logistics, and technological innovation shaping 2024 and beyond.

The WTO’s World Trade Report, published in September 2023, makes the case for re-globalisation in order to address the challenge of “trade fragmentation” that it identified earlier this year. Its tone gives the impression of trade on trial: it argues the “trade sceptic narrative” that has “gained traction” suggests that trade is an obstacle to building a more secure, inclusive and sustainable world.” The response from policy makers should be a reduction in trade restrictions that act as a barrier to free and fair trade around the world.

The WTO was first established in 1995 on the basis of a collective understanding that “fostering independence among economies [would] play a crucial role in achieving peace and prosperity.” This was the essence of the multilateralism that underpinned globalisation’s “End of the Nation State” narrative where nations would collaborate to increase wealth collectively through the free movement of capital, labour, technology and ideas, and goods and services globally.

To argue that trade has stopped conflict between nations, dialled down a nationalist rhetoric, or even addressed major social or environmental issues in the world, would be patently daft at the current time. But to argue that trade itself is the problem is equally misleading.

Russia has long regarded a western approach to globalisation as a threat to its own power and influence; China’s foreign policy power is, and always has been, projected through its economic reach – globalisation gave it the platform to extend this power. In other words, it is globalisation that has caused the return of great power conflict, not trade.

Nonetheless, if the WTO itself is putting trade in the dock, it is worthwhile looking at the case for the defence. The report lays out five principal reasons as to why trade is important and why policy makers around the world need to double down on re-globalisation:

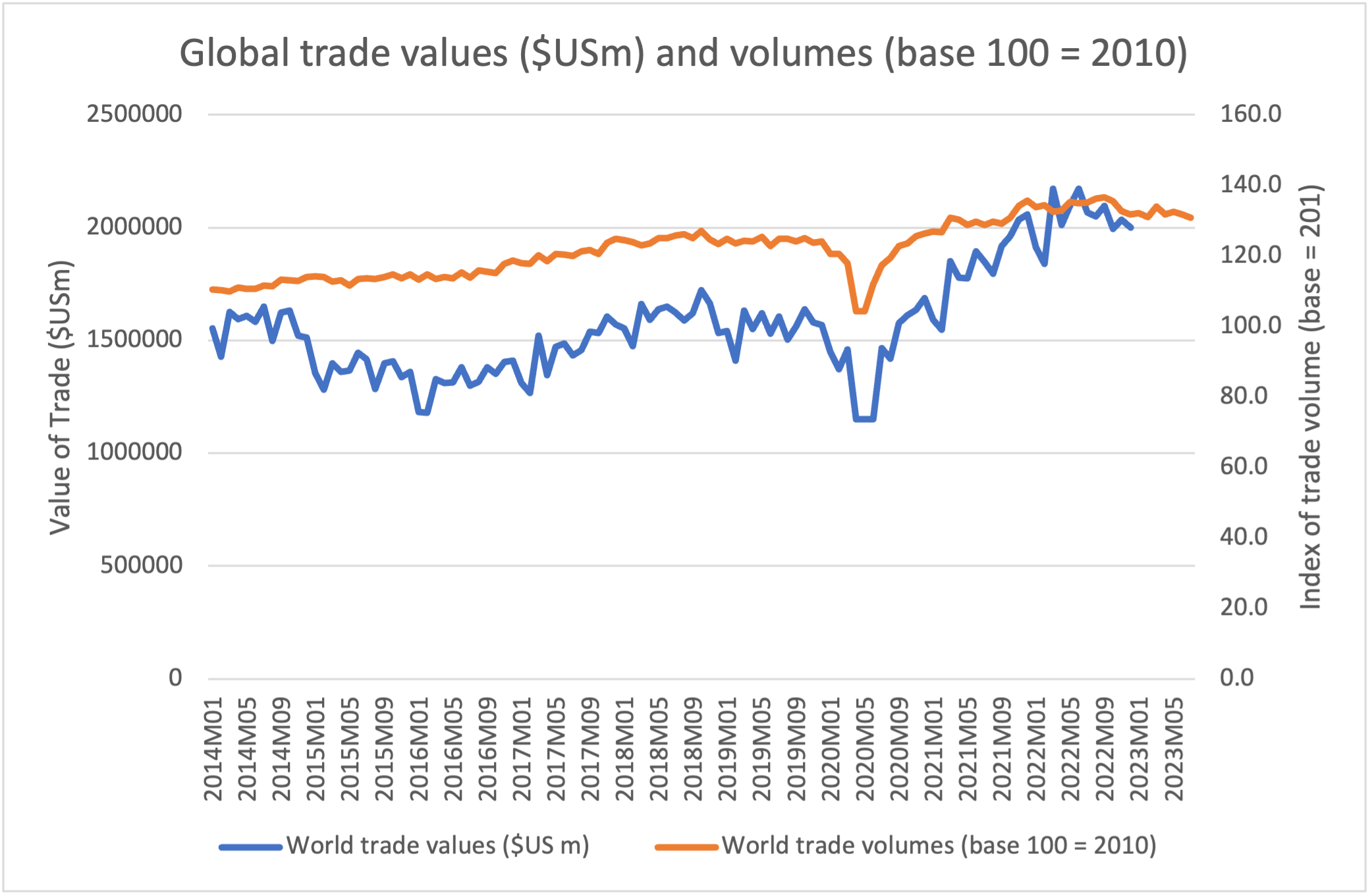

The data evidence to support this case is mixed. First, trade grew in value terms between January 2014 and the end of 2022, largely because of the impact of increases in commodity prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trade volumes also increased over the same period, but to a far lesser degree – suggesting that trade values are still reflecting inflationary pressures (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Global trade volumes and Values, 2014-2023

Source Comtrade; CBP Netherlands World Trade Monitor

Second, trade has not been used by policy makers over the past few years as means of creating a peaceful and fair economic base for the global economy to grow. Rather, it has been “weaponised” – rhetorically during the period of the US-China trade war under President Trump and literally in the period since Russia invaded Ukraine through the use of sanctions and export controls to limit Russia’s access to revenues to fund its military campaign.

This is new approach to conflict where trade itself is a key weapon in a “deterrence by denial” approach to constraining an adversary. For example, export control restrictions on military technology and dual use goods are used to deny both China‘s and Russia’s scope to develop advanced weapons capability using Western technologies. This is trade being used as a means to pull back on globalisation which has deepened and extended Great Power Conflict into geoeconomics, not just geopolitics. Trade is a part of this contested world – as it always has been, suggesting that maybe the globalisation narrative was always somewhat naïve.

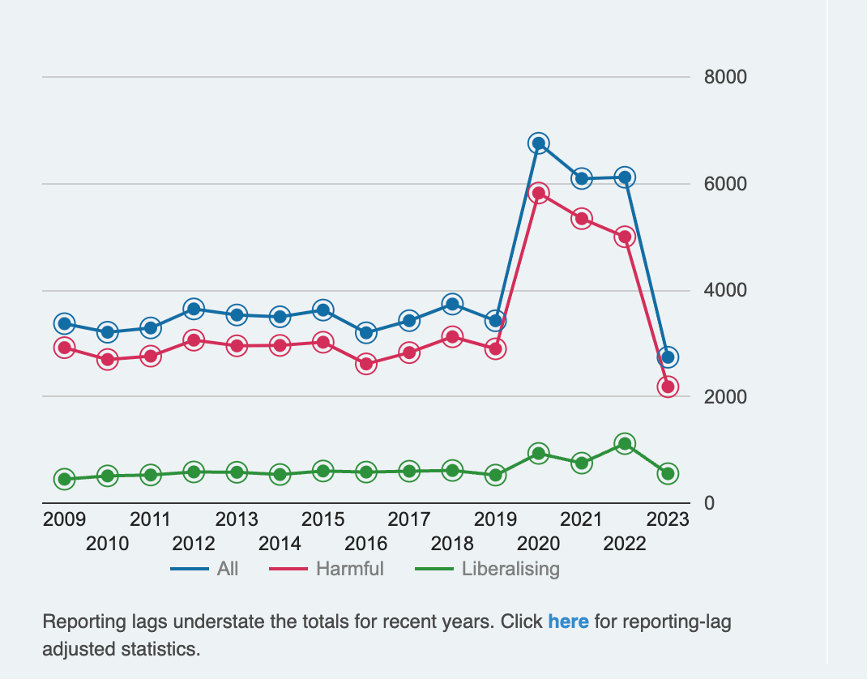

The third line of defence is that economic nationalism militates against the benefits of free trade. Interestingly, economic nationalism, if we are to measure it by protectionism, seems to have been a particularly acute problem during the Covid period (Figure 2). The rapid increase in protectionism was during 2020 with 2021 showing an increase in trade liberalisation measures and 2022 into 2023 showing a marked decline according to the Global Trade Alert.

Protectionism did rise after 2016, and this was associated with a decline in trade integration by some analysts, notably the IMF, European Central Bank and the Bank of England. However, the causal effects are harder to define – just looking at Figures 1 and 2 it’s quite easy to point out that any decline in trade was not permanent and, more importantly, was associated equally with a drop in confidence in trade resulting from fear of a trade war during the Trump administration and a global pandemic in 2020.

Figure 2: Trade protectionism vs trade liberalisation

Source: Global Trade Alert, September 23rc 2023

The fourth defence is that we need to work together if we are to solve the problem of climate change. This is certainly true, but if we were genuinely putting trade on trial, the prosecution would argue that this is not a trade point, it is a multilateral one. In trade terms, we are seeing an increase in sustainable products within the trade mix according to the IMF, but this may reflect changing production techniques and consumer preferences as much as it reflects a shift in trade. At just 8.1% of all trade, there is still a long way to go.

Defining the impact of world trade on sustainability is at best a challenge and at worst impossible. On one level, between 20% and 30% of global CO2 emissions are associated with international trade making it a major contributor to the environmental challenges the world faces. On another level, almost by definition, international trade enables goods and services to move around the world that contribute positively to climate transition. In other words, the more trade grows, the more likely it is to have negative climate impacts at least in the short term.

The fifth line of defence is that integrated value chains create inter-dependencies that pull countries together rather than separate them. According to the WTO, fewer interdependencies would be at the expense of integrating emerging economies into the global trade system. Yet it is these very inter-dependencies that deterrence by denial, and more general supply chain de-risking, attempt to unravel on national security grounds. The phrase “Supply Chain Resilience” has entered our lexicon of defence and security as the world moves from the supply chain shortages of the pandemic and its aftermath to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia and the perceived threat that China represents militarily in the Indo-Pacific.

So the case for the prosecution is arguably based on the Realpolitik interpretation of these five statements rather than a more idealistic one in the current era. World inequality is growing, economic nationalism can also be seen as a means of bringing jobs and employment back to home shores, protecting against a geoeconomic ‘adversary’ and China’s rise is a threat to the hegemony of the rules (and US dollar) based hegemony that was the essence of globalisation.

As the judge in this case, I ask you to be the Jury. My summing up would be this, however. The evidence is mixed, that much is clear from everything that has been covered. However, the questions that you, the Jury should be asking yourself, are quite clear: is it trade or globalisation that is in the docks. In either case, what are the risks if the “prisoner” is convicted, and if the “prisoner” is convicted, what is the credible alternative? How will this affect the geoeconomic and geopolitical world for the next 30 years. Will we be condemning ourselves to a future of conflict, nationalism and the separation out into at least two economic spheres of influence? Or will we be living in a more sustainable, de-risked world with friend-shoring, near-shoring and resilient supply chains? And if the latter is the case, how will the non-aligned nations – especially in Africa – use their future control of rare earth elements to their own strategic advantage?

The WTO put trade and globalisation in the dock with their report. At a recent event to a large audience in London, I asked an audience using a similar scenario whether they found the prisoners guilty or not guilty. The majority found trade not guilty and globalisation guilty. This then begs the question – what is the sentence? Increased free and unconstrained trade? Perpetual service to national security interests and decoupling? 20 years of reform to the rules-based order? Or, as the WTO might suggest, compulsory community service consisting of reglobalisation taking into account the need to engage all nations, aligned and non-aligned, in a serious debate and about social inclusion and sustainability?

What is absolutely clear is that trade has been politicised. For this very reason, the Jury can expect to be out for some time and the chances of a unanimous verdict very low.

Dive into the future of UK & DE freight: Adaptation, green logistics, and technological innovation shaping 2024 and beyond.

Join Dr. Rebecca Harding in a crucial discussion on sustainability in economics. Dive into why regulators must evolve GDP metrics to include sustainability for an accurate portrayal of our climate challenges and the journey towards actionable global solutions.

Explore the intricate relationship between trade fragmentation, geopolitics, and supply chain resilience with Dr. Rebecca Harding. Learn why understanding the political landscape is crucial to making economic sense and how strategic trade is shaping the 21st-century battleground.

Uncover the strategic necessity of Supply Chain Resilience in our latest piece by Dr. Rebecca Harding. Discover how today’s trade becomes a domain of warfare and why intelligence in supply chains forms the New Tradecraft in safeguarding national security.

Discover how biometric technology could revolutionize global trade, offering seamless and secure cross-border transactions by reducing inefficiencies at customs and immigration, with real-time tracking and smart contract integrations, promising a future of frictionless international commerce.

Contact

Services

About

Insights

Rebecca’s Bio

Terms and conditions

Privacy